Occupational Health | Alert | No.461 V 1 | 14 October 2025

Effective management of heat risks for workers

Summary

- Heat exposure continues to be a risk that needs to be managed for workers across the resources sector.

- Heat stress can cause a medical emergency and, if not properly prevented or treated, it can be fatal.

- Each year as we approach the summer period, Resources Safety and Health Queensland releases updated information on heat exposure and related risks. This alert includes information and links to materials for all resources sector sites to review and take appropriate action to ensure effective management of heat risks for workers.

Issue Explained

- If the body is overexposed to heat conditions a worker begins to suffer from heat-related illness.

- Exposure to heat can lead to dehydration, fainting, heat rash, swelling, cramps, exhaustion (including fatigue, nausea and vomiting, clammy skin and weakness). Heat stroke is a medical emergency and may lead to confusion, disorientation, convulsion, loss of consciousness and death.

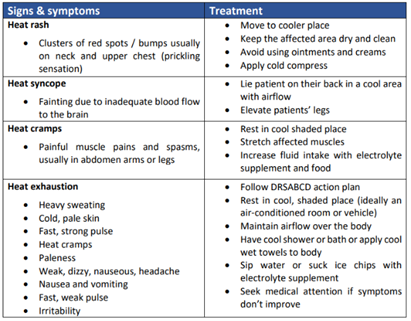

Figure 1: Symptoms of heat-induced illness

- Several factors may contribute to heat stress or heat-related illness, such as the temperature, humidity and movement of the surrounding air, the type and duration of the work activity and an individual person’s physical condition.

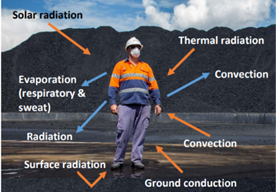

Figure 2: Heat factors impacting a worker

- Obligation holders, site managers and workers need to be aware of the risks of heat stress and know what to do to prevent it, or treat it, should it occur.

- Ahead of the hotter months, those with safety and health obligations should:

- review site preparedness for managing heat exposure

- consult with and communicate how heat exposure is to be managed with workers

- review existing controls to prevent negative health outcomes from heat exposure

- ensure emergency preparedness is appropriate, should a worker become heat affected.

- These obligation holders must ensure that exposures to heat are being effectively managed to an acceptable level of risk at their workplace/sites.

- A risk assessment assists in determining the severity of heat exposure, action required, whether the existing controls are adequate and what action should be taken to control the risk to an acceptable level.

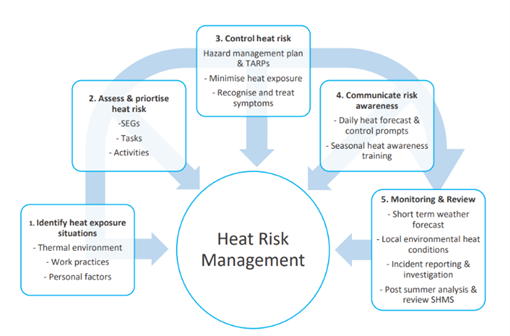

Figure 3: Basic requirements for an effective Heat Management Plan

Learnings

1. Preventing heat-related illness

- The consumption of cool, potable water readily accessible to the work area is the preferred method of hydration.

- Small quantities of water at frequent intervals (15-20 mins) is recommended for practical fluid replacement rather than the intake of large amounts per hour.

- Consumption of energy drinks should be limited or taken in moderation, as excessive consumption can result in a salt, particularly potassium, imbalance. Excessive consumption of drinks containing caffeine including tea, coffee, energy drinks and cola may have a diuretic effect in some individuals and should also be taken in moderation.

- Pre and post shift hydration testing can be used where a high risk is identified. A response plan should be activated when testing indicates dehydration is occurring. Hydration testing could be a valuable tool to assess a worker’s ability to return to work following a heat related incident.

- Including crushed ice in drinks used for hydration purposes is part of an effective strategy for maintaining reduced core body temperature.

- Hydration needs are dependent on the type of work being done and other environmental factors.

- Maintaining a healthy diet and consuming food prior to attending work, as this provides energy and is a major source of electrolytes. Adequate dietary intake should usually preclude the need for electrolyte supplements.

- Workers who may require an increased fluid intake and may require an effective electrolyte replacement include those with elevated heat risk, such as those working:

- Outdoors in direct sun (such as a rig worker).

- In a process that generates heat (such as a boilermaker).

- In physically demanding roles.

- In confined or partially confined space.

- While wearing protective clothing such as disposable coveralls or arc flash protective clothing.

- Workers should monitor their fluid need by observing any changes in urine colour, which is typically pale yellow if the person is adequately hydrated. Dark yellow urine is usually an indication of dehydration and a need for an increased water intake.

- Certain foods, medications and vitamin supplements may change urine colour even when hydrated. Urine colour charts in bathrooms can assist with self-assessment of hydration status.

- Workers should be allowed adequate rest periods in a cool place to lose excessive heat build-up which can raise core temperature.

- Establish work-rest schedules, encourage workers to pace themselves to cater for individual’s needs.

- Additional work crew during hotter months, is an effective control for worker rotation (e.g. summer lease-hand).

- Clothing should be the minimum which meets safety requirements.

- Evaporation of sweat is the main way the body can lose heat when working in hot conditions and wearing clothing can reduce the effectiveness of this cooling mechanism. Consideration should be given to selecting clothing fabric that promotes the moisture permeability and air flow, without compromising other protective qualities such as UV radiation.

- Ventilated safety vests should be used, where appropriate.

- Workers should be monitored for signs of heat stress.

- Workers must be acclimatised before being exposed to high heat stress conditions for full shifts.

- Acclimatisation allows the body to adapt to a hot work environment.

- Acclimatisation to hot working conditions can depend on several factors, such as background, fitness, age, medications, fatigue/sleep, health etc (refer to QGN32 Appendix 1 for comprehensive list).

- Consideration should be given to workers in high-risk positions or rosters such as FIFO/DIDO or lone worker arrangements

- There is a suggested acclimatisation schedule outlined by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- Refer to QGN32 Appendix 6: Heat acclimatisation protocols for suggested management protocol.

Figure 4: Exposure to working in the heat

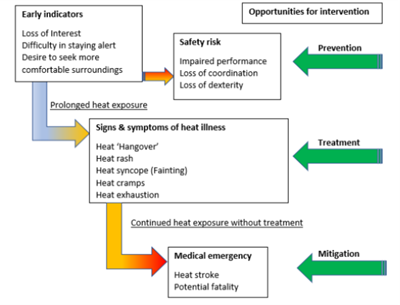

Figure 5: Progression of heat-related effects

2. Control measures for heat-related illness may include:

- Controls include modifying the environment to suit the work, modifying the work to suit the environment or a combination of both. Sites should:

- Reduce radiant heat sources using insulation, spot cooling or shielding.

- Locate potable water and ice machines within easy access for workers to hydrate regularly.

- Use mechanical aids where possible (e.g. using cranes and forklifts), to minimise physical exertion in heat.

- Plan work activities to include periods of acclimatisation for workers returning after prolonged absence.

- Provide a cool refuge for workers, preferably air-conditioned, to enable regular rest breaks in cool areas such as vehicle cabins, crib rooms and control rooms.

- Provided there is cool airflow available, erect portable shades as refuge areas for temporary or remote work locations (noting cool air flow is essential). Increase air movement by the installation of mechanical fans and introduce cooling fans where possible.

- Reschedule high physical work activities to cooler times during the shift.

- Select clothing options which offer ventilation openings and permeable fabric.

- Introduce a buddy system and/or task rotation.

- Train workers on heat identification, control and emergency response.

- Appropriately incorporate heat in the reporting of incidents, specifically heat related incidents as well as a potential contributing factor in any incidents.

- Using exhaust ventilation to remove steam in high humidity operations such as quenching.

- Consideration should be given to the development of Heat Stress Management Plans or Triggered Action Response Plans (TARPs) for controlling heat exposure on a shift-by-shift basis. The action trigger values should be aligned to local heat conditions such as using local weather monitoring and forecasting of ambient temperatures (e.g. national Bureau of Meteorology (BOM)); and supplementing this with the use of portable monitoring devices to accurately assess the thermal conditions at particular positions (e.g. in the pit with limited cross breezes, or working on surfaces which reflect radiant heat, or near objects which generate heat).

3. Review the controls for heat-related illness

- Control measures must be reviewed to ensure they are working as planned.

- Are the available controls used by workers when needed?

- Are the controls effective at reducing core body temperatures?

- Is there a better control that could be reasonably practicably implemented?

4. Management for heat-related illness

- Workers should be trained on how to recognise the signs of heat related illnesses and provide effective treatment in a timely manner.

- The site must provide for first aid facilities and emergency response capability at a worksite; that is suitable for responding to cases of heat illnesses caused by exposure to work in the heat.

- Consider items required for the rapid cooling of a person and how these could be deployed by the emergency response team (ERT) or how portable emergency heat treatment kits could be made available at remote work sites (e.g. exploration drilling site), to be used by first responders during the critical first 30 minutes, while waiting for the ERT to arrive.

- Examples of portable heat stroke kit contents include an esky, iced and damp towels, first-aid instant cold packs and iced water. Further examples of a portable heat stroke kit is, Appendix F of the summary report of audits and inspections QGN32: Heat.

Investigations are ongoing and further information may be published as it becomes available. The information in this publication is what is known at the time of writing.

We issue Safety Notices to draw attention to the occurrence of a serious incident, raise awareness of risks, and prompt assessment of your existing controls.

References and further information

- Safety bulletin 191: Managing heat exposure in coal mines

- Safety bulletin 91 – Heat Stress

- Safety alert – Heat Stress

- Guidance Note QGN32 - Managing Exposure to Heat in Surface Coal Mines and Surface Areas of Underground Coal Mines

- s18 Management of Heat in Underground Coal Mines

- Petroleum and Gas (Production and Safety) Act 2004

- Requires all reasonable steps to be taken to ensure no person or property is exposed to a level of risk in relation to the operating plant that is more than an acceptable level.

- Petroleum and Gas (Safety) Regulation 2018

- Queensland Coal Mining Safety and Health Regulation 2017:

- This sets out specific provisions for both surface and underground coal mines with respect to the management of heat. In summary:

- An underground coal mine SHMS must provide for:

- ensuring the health of persons in places at the mine where the wet bulb temperature exceeds 27°C [s369(1)]

- a methodology for calculating effective temperature at certain locations [s364 and 370]

- preventing persons from working at the mine where the effective temperature exceeds 29.4°C unless under specific circumstances [s369(3)].

- A surface coal mine SHMS must include a procedure for protecting persons from heat related illness [s143].

- In addition to this safety alert, Recognised Standard 18 - Management of heat in underground coal mines was released in August 2021 and Guidance Note 32 for management of heat at surface coal mines was released in January 2022.

- Queensland Mining and Quarrying Safety and Health Regulation 2017:

- s143 sets out specific provisions with respect to management of heat

- The site senior executive for a mine must ensure the mine has a system for managing the risk to persons from heat in places at the mine where the wet bulb temperature exceeds 27ºC.

- The site senior executive for a mine must also ensure a person is not exposed to a wet bulb temperature exceeding 34ºC at the mine unless the person is—

- (a) engaged in work to reduce the temperature and authorised by the person’s employer or supervisor to carry out the work; or

- (b) a mines rescue member carrying out training or emergency response under procedures documented in the system; or

- (c) being evacuated in an emergency.

- The following resources provide readily available information, assessment tools and processes for the assessment of heat exposure and heat related illnesses:

- Heat Stress Calculator - WorkSafe Queensland.

- A Guide to Managing Heat Stress: Developed for Use in the Australian Environment - Australian Institute of Occupational Hygienists (AIOH).

- Managing the Risks of Working in Heat Factsheet - Safe Work Australia.

- Working in Heat - Safe Work Australia

- AIOH Basic Thermal Risk Assessment

- Heat stress information & tools - WHSQ

- Managing the risk of working in heat information & tools – Safe Work Australia

Contact: communications@rshq.qld.gov.au

Issued by Resources Safety & Health Queensland

Placement: Place this announcement on noticeboards and ensure all relevant people in your organisation receive a copy.

Find more safety notices

Search the hazards database