Mines safety bulletin no. 88 | 23 February 2010 | Version 1

Management of dust containing crystalline silica (quartz)

1.0 Introduction

Respirable dust (ie dust small enough to penetrate the very small breathing vessels within the lung) containing crystalline silica is known as respirable crystalline silica (RCS). The predominant form of crystalline silica is quartz. In sufficient quantity RCS can cause silicosis; an irreversible, progressive and potentially fatal condition that results in healthy lung tissue being replaced by fibrous scar tissue. Scientific evidence also suggests that silicosis can lead to lung cancer. These diseases can develop after many years of exposure to high dust levels.

A survey questionnaire aimed at assessing the potential for exposure to excessive levels of RCS was sent to 420 small to medium sized metalliferous mines, quarries and exploration sites in Queensland. The questionnaire was prompted by the finding that some quarries visited by the Mines Inspectorate do not have adequate health surveillance in place for their workers, nor have completed an assessment carried out to measure RCS exposure.

Survey results:

| Operation | Questionnaires sent | Reply received | % Respondents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quarries | 177 | 85 | 48 |

| Small to medium mines | 188 | 25 | 13 |

| Exploration sites - coal | 30 | 10 | 33 |

| Exploration sites - non coal | 25 | 12 | 48 |

| Total | 420 | 131 | 31 |

Note this report is based on feedback received from 131 sites, accounting for 31% of all sites surveyed.

2.0 Survey findings

The survey findings indicate that many sites may not be adequately addressing the risk of RCS exposure resulting in the potential for adverse health effects from respirable crystalline silica Chronic exposure to respirable crystalline silica, even at relatively low levels, may lead to chronic silicosis many years after a worker has retired.

A significant number of operations did not respond to the survey. This may mean there are many more sites without adequate controls in place.

Significant findings of the survey are summarised as follows:

- 32% of sites didn't know if their rock contained free silica

- 21% of sites didn't know how much free silica was present

- 78% of sites believed onsite workers were exposed

- 98% of sites rated onsite dust levels as low to medium

- 52% of sites carried out personal monitoring

- 43% of sites provided results back to workers

- 14% of sites have carried out monitoring on one occasion

- 19% of sites carry out monitoring annually

- 69% of sites use respiratory protection during dusty conditions

- 45% of sites do not perform respiratory protection fit testing

- 46% of sites provide health surveillance for workers at 1 to 5 year intervals

- 67% of sites provide training about the hazards associated with RCS.

Observation of visible dust should not be the only indicator to demonstrate that respiratory protection is necessary. Invisible fine dust particles are the most hazardous, highlighting the importance of personal monitoring to identify job types and specific tasks requiring control measures.

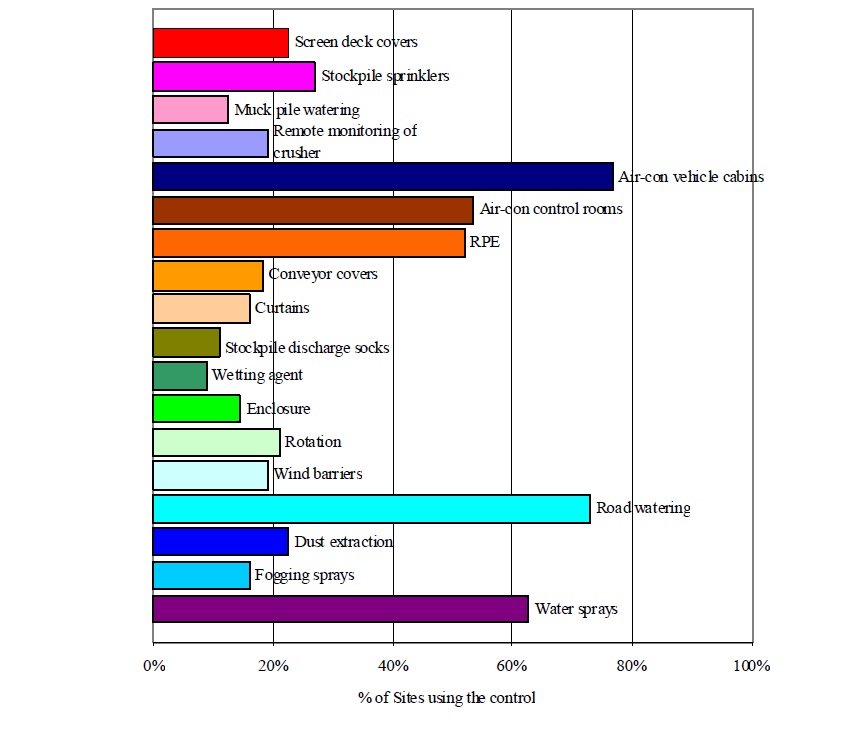

The types of dust controls used by respondents are detailed in Figure 1 below.

There is a high level of reliance on air-conditioned vehicle cabins. However many standard air conditioning systems don't provide an effective barrier or offer acceptable protection against RCS, due to the small size of the dust particles concerned. Therefore it is necessary to carry out monitoring in enclosed cabins to verify that filtration systems are effective.

3.0 Control strategies

The order in which controls are implemented must follow the hierarchy of controls – elimination, substitution, engineering, administrative and lastly personal protective equipment. It is critical that awareness of the potential health effects from respirable dust, dust control and health surveillance be improved.

4.0 Monitoring

Where there is a risk of exposure, monitoring should be carried to determine baseline levels of exposure for each job or task. Personnel should be grouped into similar exposure groups (SEGs) - groups of workers with similar exposure levels. The need for ongoing monitoring is based on the level of exposure in relation to the occupational exposure standard (OES) or general exposure limit. Schedule 5, of the Mining and Quarrying Safety and Health Regulation 2001, has assigned an exposure limit (8h, time weighted average (TWA)) at 0.1mg/m3.for RCS. If shifts are longer than 8h this limit shall be reduced accordingly. Simtars' Occupational Hygiene, Environment and Chemistry Centre, Adjustment of Occupational Exposure Limits for Unusual Work Schedules, provides guidance on how to reduce exposure limits where shifts are longer than 8 hours. The suggested ongoing monitoring frequency, based on maximum and average concentrations in relation to the OES, is provided in Table 1.

| Concentration range | Monitoring frequency |

|---|---|

|

Average concentration < 10% of the OES and maximum concentration < 10% of the OES | Monitor once every 5 years (baseline survey) |

|

Average concentration 10-25% of the OES and maximum concentration 10-25% of the OES |

Monitor once every 2 years or continuously# sampling personnel once every two years |

|

Average concentration < 50% of the OES and maximum concentration 25-50% of the OES |

Monitor once per year or continuously# sampling personnel once per year |

|

Average concentration < 25% of the OES and maximum concentration >100% of the OES Average concentration < 50% of the OES and maximum concentration >50% of the OES |

Monitor twice per year or continuously# sampling personnel two times per year* |

|

Average concentration >50% of the OES and maximum concentration >100% of the OES |

Monitor quarterly or continuously# sampling personnel four times per year* |

**the maximum and average concentration refers to that for a SEG

#continuous sampling refers the establishment of a random on-going sampling program

*mandatory respiratory protection program should be in place and follow hierarchy of controls

Notes:

Preliminary monitoring should be carried for each SEG to establish baseline exposure.

These monitoring frequencies apply to processes that are fairly constant. Where there is a significant change to a process each different process may have to be monitored.

5.0 Health surveillance

Where exposure to RCS may cause an adverse health effect, health surveillance is required. Health surveillance for RCS should include the following:

- Demographic information (date of birth etc.) should be collected, as well as information relating to occupational history (descriptive job title with relevant start and finish dates) and medical history.

- The worker should be informed of the potential health effects associated with RCS exposure.

- A physical examination should take place, with emphasis on the respiratory system.

- A standardised respiratory questionnaire should be completed.

- Standardised respiratory function tests should be conducted, as well as a chest X-ray (full size posterior-anterior view).

- Records of personal exposure monitoring should be kept with the health records of the worker.

Health surveillance should be conducted on commencing work in a job where exposure to RCS may cause an adverse health effect. The frequency of health surveillance, based on RCS exposure levels, should be as follows:

- Follow-up evaluation within 12 months: Evaluate need for repeat chest x-ray at this time.

- If exposure is < 0.05 mg/m3, assess need for frequency of future follow-up evaluations.

- If exposure is equal to or greater than 0.05 mg/m3 for less than 10 years, follow-up evaluation every 3 years.

- If exposure is equal to or greater than 0.05 mg/m3 for 10 or more years, follow-up evaluation every 2 years.

- An exit evaluation should be conducted when the worker leaves their job.

6.0 Respiratory protective equipment (RPE)

Where there is a likelihood of exposure exceeding 50% of the exposure standard, a mandatory respiratory protective equipment program should be put in place until exposures are reduced using higher order controls.

Respiratory protective equipment programs should conform to AS/NZS 1715:2009, 'Selection, use and maintenance of respiratory protective equipment'. The program should include a 'clean shaven policy' (if negative pressure respirators are used), fit testing and training.

7.0 References

- Mining and Quarrying Safety and Health Regulation 2001.

- Simtars, Queensland Government, Occupational Hygiene, Environment and Chemistry Centre, Adjustment of Occupational Exposure Limits for Unusual Work Schedules, viewed on 23 February 2010.

- Australian Institute of Occupational Hygienists (AIOH), position paper on Respirable crystalline silica and occupational health issues, 2009 - viewed on 23 February 2010.

- World Health Organization (WHO), Global Workplan of the Collaborating Centres in Occupational Health for 2009-2012, Table of Priorities, 2012 - viewed on 23 February 2010.

- Safe Work Australia, Guidelines for Health Surveillance NOHSC: 7039, 1995 - viewed on 23 February 2010.

- American Industrial Hygiene Association (2006), A strategy for assessing and managing occupational exposures. Third Edition. American Industrial Hygiene Association Exposure Assessment Strategies Committee.

- ACOEM website.

Contact: minesafetyandhealth@dnrm.qld.gov.au

Issued by Queensland Department of Employment, Economic Development and Innovation

Find more safety notices

Search the hazards database